01

Bhikkhunis

Golden Era of Bhikkhunis Sasana….

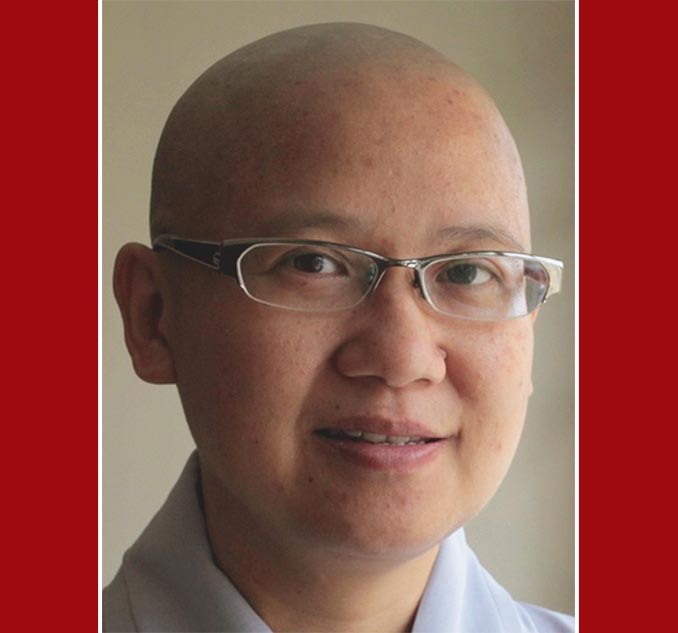

Most Venerable Bhikkhuni Fa Xun

World’s Famous Teacher and Author in Singapore, Malaysia and Western Australia, Vice -Principal of the Nuns’ Campus of the Buddhist College of Singapore

During the “golden age” when the Buddha was alive, many members of his saṅgha (Buddhist community) were able to attain enlightenment. In Hindu society during the Buddha‟s time, women‟s place was in the home and their primary role was to bear children. However, the Buddha affirmed that women have the same capacity as men to walk the spiritual path and attain enlightenment. The Buddha created a Bhikkhunī saṅgha (nuns order) parallel to the Bhikkhu saṅgha (monks‟ order), and placed men and women on equal terms in his teachings. This Bhikkhunī saṅgha provided an alternative community for women which freed them from familial constraints and encouraged their spiritual pursuits. They shaved their heads, put on the robes, and joined the Bhikkhunī saṅgha to live a mendicant life. It must be acknowledged also that during the Buddha‟s time, some women chose to join monasteries out of destitution. The diligent Bhikkhunīs proved women‟s potential for devotion, self-sacrifice, courage and endurance. They demonstrated real spiritual ability and became revered teachers and gained respect from the society. The Emperor Asoka even enrolled his daughter, Saṅghamitta into the saṅgha. Living a monastic life was highly valued by the society. Since then, many women have left their homes to follow the Buddha‟s footsteps.

Stereotypical “Traditional” Views of Bhikkhunīs….

The social status of the Bhikkhunīs began to decline after the passing of the Buddha and the withdrawal of royal patronage. They were generally deemed to be a group of helpless and powerless victims, “failures” or “social rejects”‟. Chinese literature and drama usually portray Bhikkhunīs as escapists, negativists, pessimists, “losers” in love and as failures in marriage or life. For example, in the famous Chinese classic Dream of the Red Chamber, monastic were portrayed as “losers” and “victims”. In Burma, there is the proverb, “Buddhist Nuns are those women whose sons are dead, who are widowed, bankrupt, in debt, and broken-hearted” (Kawanami 2000, p. 136). Becoming a Bhikkhunī was represented not as a choice but as a circumstance or fate which they suffered. Bhikkhunīs were seen to have been forced into monasticism due to setbacks they had encountered in life: these could be bankruptcy, being in debt, living in poverty, inability to find a husband or a broken heart from a failed relationship. Widows joined the monastic order due to social pressure to maintainchastity and poverty. Their desperate situation led them to join the monastic order as a last resort. Becoming a Bhikkhunī was seen as a kind of social suicide. Such negative stereotypes of Bhikkhunīs have been reported by various scholars such as Tsung (1978), Chern (2000), Crane (2004) and Cheng (2007). In contemporary times, negative portrayals persist. There are numerous studies that suggest that women choose to become Bhikkhunī in order to escape from unfortunate lives. Tsung conducted fieldwork in Taiwan before 1978, and found that the „traditional‟ Bhikkhunīs (those who had joined the monastery before her fieldwork) were usually older and poor. They had usually been abandoned or pushed into monasteries by their families. Most of the Bhikkhunīs in Tsung‟s sample chose nunhoodin order to escape from their stormy lives. They had experienced painful events that made their life undesirable; in great disappointment and pain, they „escaped‟ into the nunnery (Tsung 1978, p.247).

New Views of Bhikkhunīs….

The low social status and the negative image of Bhikkhunīs were radically challenged in the late 1980s when a group of young women in Taiwan shocked their friends and families by joining monastic orders. These women were not social rejects: they were smart and successful in school, and were described as bright and attractive; they had been about to start promising careers. Most had good marriage prospects. Their decision to become Bhikkhunī was received with wide-eyed disbelief by the public. Why would they leave their family and friends, a promising career, and financial security to become a Bhikkhunī? The act of choosing to become a Bhikkhunī by this group of young women questioned and challenged the social stereotype of Bhikkhunīs. In Tsung‟s (1978) representation, the Bhikkhunīs in Taiwan were a group of social rejects; in contrast, in Crane‟s (2004) report, Bhikkhunīs were “young and successful” women who had chosen to become Bhikkhunī, as a way of rejecting marriage and conventional understandings of womanhood. Recent ethnographic works by various scholars indicate that Bhikkhunīs are not “escapists” or “failures”, but rather, they are active agents making their own choices. For example, many Bhikkhunīs in Taiwan, interviewed by Chern, claimed that they did not want to “recognize and admit fate” (Chern 2000, p. 290), to follow the traditional path of being daughter, wife and mother; they questioned the traditional roles of motherhood and housewife and they questioned even more intensely the “meaning of human life” (Chern 2000, p. 284). They attempted to practise a life “beyond good motherhood and housewife” (Chern 2000, p. 290). Chern found that the Bhikkhunīs rationally and enthusiastically chose to leave home and enter the monastery. They were making their own choices and wanted to live an active and socially engaged life. They wanted to cultivate independence and be responsible fortheir own lives (Chern 2000, pp. 279-290).

Both Chern and Cheng reported that the Bhikkhunīs in Taiwan questioned the standard life pattern of females in the patriarchal social system. They did not wish to be caught in such a system and decided to live a life of their own (Chern 2000, p. 285 and Cheng 2007 pp. 111-112). Thus, until recently, Bhikkhunīs were seen as a group of passive victims, as social rejects; they were people who had renounced the world because they had failed in it. However, by the 1990s, some young and successful women were taking up the role of Bhikkhunī as active agents and as achievers in modern society. In Cheng‟s and Chern‟s samples, the Bhikkhunīs from some distinctive monasteries in Taiwan – such as Luminary Bhikkhunī Saṅgha (Xian Guang Ni Sheng Tuan), Buddha Light (Fo Guan Shan) and Dharma Drum (Fa Gu Shan) – were usually younger and better educated. They were represented as active agents making their own choices, choosing to become Bhikkhunīs against the backdrop of the hegemonic Han patriarchal ideology.

The Therīgāthā….

The Therīgāthā is a collection of 73 poems consisting of 522 verses reputed to be the record of the experiences of the Buddha‟s first female followers, all of whom are accredited with arahant-hood. There are many positive images of women in the Therīgāthā. This seems to prove that Buddhism, since its very beginning, has acknowledged the authority and equality of women in spiritual practice. The collection includes clear, unambiguous and straightforward accounts of women with high spiritual attainment. The Therīgāthā is a unique testimony to the experiences and aspirations of the Bhikkhunī saṅgha. The Therīgāthā was passed on orally for four centuries before being committed to writing inSri Lanka in the first century B.C.E in the Pāḷi language. 8 Although it is impossible to know with certainty who composed these texts, or when and where they were composed, Kathryn Blackstone maintains that it is the “only canonical text in the world‟s religions that is attributed to female

authorship and that focuses specifically on women‟s religious experiences” (Blackstone 1998, p. 1). Maurice Winternitz also believes that the great majority of the poems were composed by women because in the patriarchal context in which it was written, monks would never have had so much empathy with female members in the community (Winternitz 1972, p. 102). Within Buddhist Theravāda tradition, these verses have been regarded as the historical utterances of women who have gained perfect enlightenment.

Global Visitors

Nuns

- Targets

- Challengers

- Retreats

- Values

Main Products

- Bhikkhunis Magazine

- Mettavalokanaya Magazine

- Shifu International

- Buddhist Website

Bhikkhunis

- News

- Famous Nuns

- Famous Temples

- Videos